A Personal History of Visual Programming Environments

Part of my journey to becoming a software engineer and working in tech is due to the fact that while in music school, I had exposure to visual programming environments like Pure Data / Max and Quartz Composer. Hindsight being 20/20, I probably would not have been as enamored with the idea of creating software - and learning how to program it - had I not been exposed to these environments.

I learnt these visual programming environments because I wanted to get closer to realizing the sounds and visuals that were in my head, and I wasn’t able to realize using the ready-made, domain specific software programs that were available to me.

I needed to get closer to writing software than using it - though this vocabulary was not available to me at the time.

The music program I attended had various performing ensembles - classical, choral, jazz; even a rock ensemble!

By far the most unique of these was the Midi Band. Around 8-10 musicians and two sound engineers would surround themselves with electronic drums, a Midi saxophone, Midi guitar, an excessive amount of electronic keyboards, and other electronic music arcana. We’d sometimes play to a backing or a click-track provided by a laptop.

Since this was all Midi, the only way you could hear it was to have the audio piped through a personal headphone mixing station, and then through large speakers so that the audience could actually hear the music.

At various times while being in the music program, I would either play the Midi Bass, or be a sound engineer for the ensemble. During my senior year, I became interested in making interactive visuals that would play along with the music that the ensemble was playing; which was mostly music with an electronic component (I arranged a version of Depeche Mode’s “Behind the Wheel” for the group).

One of my favorite blogs at the time was Create Digital Media - a treasure trove of articles on how artists and musicians were using hardware and software in their creative practices.

This was where I learned about Quartz Composer - a wonderful piece of software that came bundled with my Mac’s OS. Seeing the dynamic, magical visuals that other people were able to create with Quartz Composer made me want to dive in. The idea that it was possible to create concert-level quality of live visuals with this free program that came on my computer was captivating to me.

Quartz Composer

Used a lot by designers to create interactive demos and presentations, it went on to inspire Facebook’s Origami Studio (which originally was a Quartz Composer plug-in. It also found a niche home in the VJ community, where it was used to create absolutely breathtaking dynamic visuals. There was never a whole lot of resources on how to use it…you just kind of had to fuck around and find out until you got something that you thought looked cool. There were a few forum posts that were helpful with getting started, but sadly the only book at the time on the subject was written in Japanese.

That said, the visuals that some of the artists I found were truly inspiring, and I was able to get far enough along with it to create visuals for the Midi Band performances.

I’d take an audio line from the mixer board and plug it into my computer with an audio interface like this one:

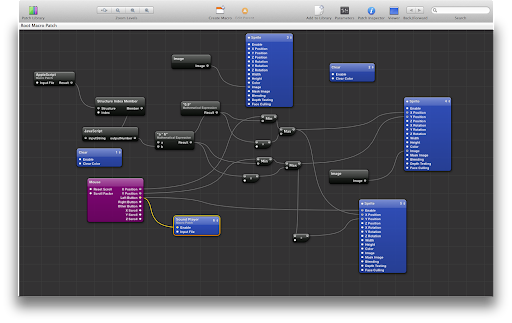

I’d route the audio into Quartz Composer, and use the amplitude / frequency of the signal to control the visuals. I could do this all by creating and connecting objects together on Quartz Composer’s canvas:

…and would use the knobs and keys on a MIDI keyboard controller to adjust visual parameters or trigger visual sequences.

Because you could connect anything to anything just by dragging virtual patch cowards between objects,you could quickly see how these different connections affected the visual output.

Quartz Composer allowed non-technical people to create powerful, rich, interactive systems without writing any code yourself. It was truly a predecessor to contemporary no-code software, and deserves to be recognized as such. QC was one of a kind, and I continually mourn it’s unsettling - much in the same way that HyperCard users mourned that tool’s passing as well.

If you are working on a native Mac app that’s a spiritual successor to Quartz Composer, please reach out! nicholasarner@gmail.com

PD / MAX

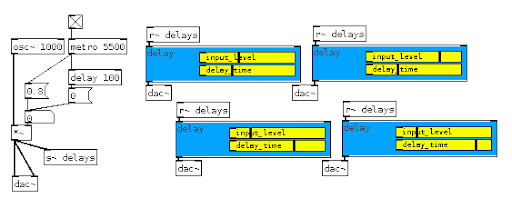

During my college classes on electronic music and composition, I was exposed to PureData. PureData is a free and open-source programming environment for sound synthesis (though plugins exist for visuals, too). Though the interface is rather barebones, it’s canvas allows for complex audio synthesis patches to be created visually, without having to write any code:

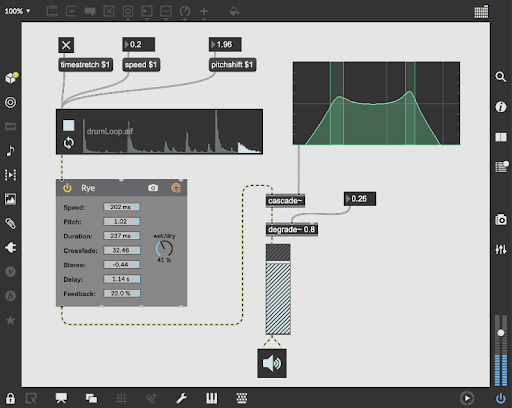

Eventually, I made the jump to PureData’s paid cousin, Cycling 74’s Max. With a slick interface, packaging system, and regular updates; it’s a Swiss Army knife for anyone working with interactive media.

PD and Max allowed me to make the jump from using software for composing and sound design to using making small programs to manipulate data and control things like DSP processes and effects at a fundamental level. My actions on the Max canvas, slicing and stretching and pulverizing sound samples, had an effect on me - I began to understand how computers could be capable of allowing me to have a more immediate and intimate connection to the medium I was working with.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but this would put me on a path to understanding a fundamental potential of computers - the ability to manipulate data in a way that would amplify my creative goals.

It also opened me to the world of OSS communities….PD and Max users would share mini programs (“patches”) in various forums that you could download and run yourself. Modifying these patches and figuring out how they worked was both how I learned about fundamental audio synthesis principles, and how the software itself worked.

Asteroid

Many years after these initial forays into visual programming environments for creative applications, I had learned to program, and had been working as a MacOS and iOS engineer for a few years.

I eventually joined a nascent startup, Asteroid, as Employee One. The product we were working on was a native Mac app, written in Swift, that would let you create ARKit interactions without writing any code.

One of my main contributions was creating a node-based interface where you could add objects to a canvas that would power your ARKit interaction flows and connect them together to define the behaviors of the interaction.

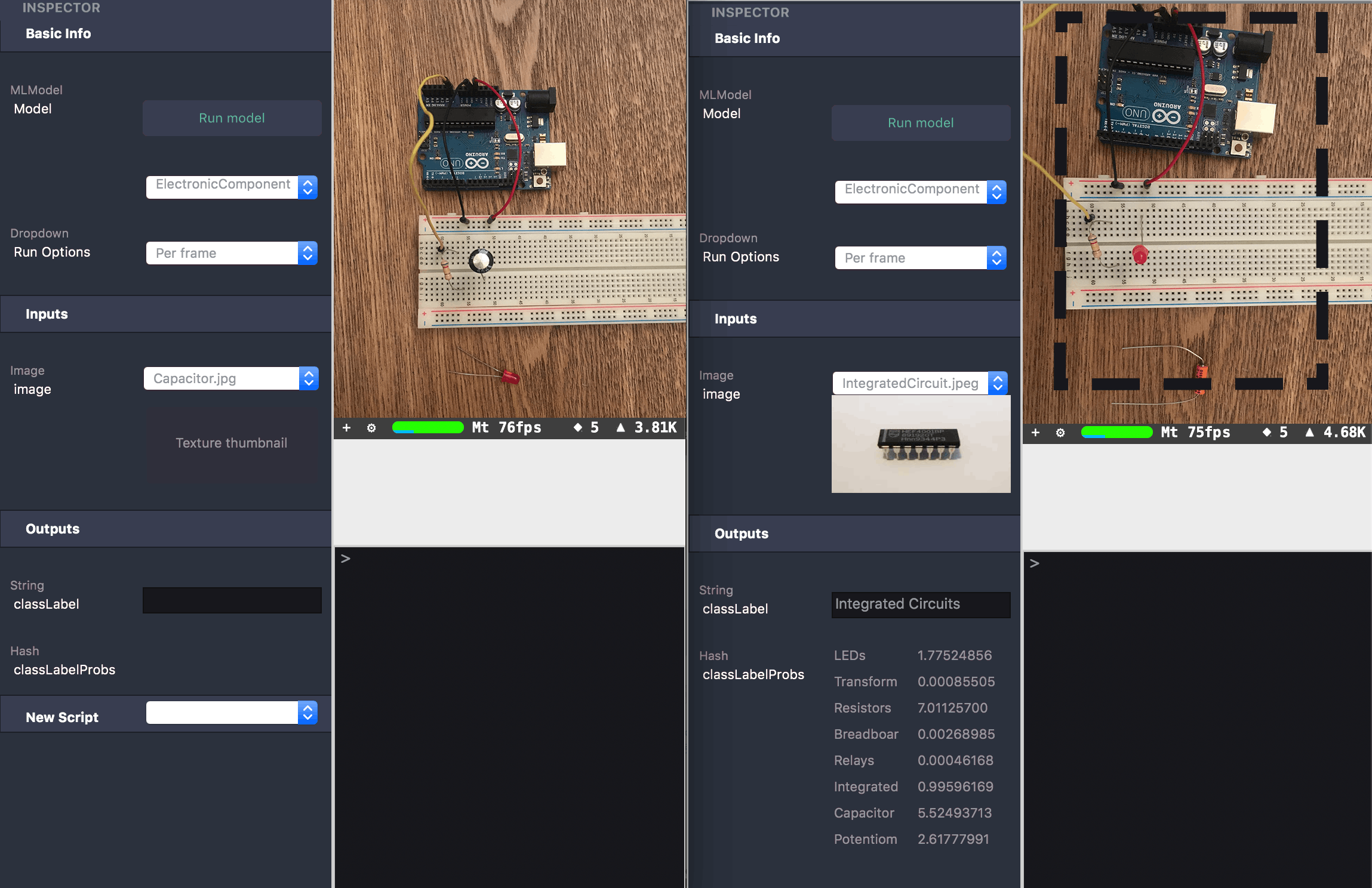

For example, you could create a camera object, and connect it to an ML object. The camera would send frames to the ML object and run them through a CoreML classifier.

FDepending on the type of ML model that was being used, you could do different things with the results. For example, one of the demos I made used an ML model that would detect different hand gestures. Depending on what type of gesture was detected (like an OK-sign, or a thumbs up), a corresponding 3D Emoji asset would appear in the field of view.

When you were done creating your interactions in the visual canvas, you could export it out of our Mac app, and have a fully functioning ARKit-based Xcode project that was ready to deploy a working app to your iOS device.

I made several demos, including a yoga pose detector, and an app that could recognize electronic components, such as resistors or capacitors.

The visual, node-based canvas allowed for fairly complex ARKit-based interactions to be created without having to write any code. Once you had prototyped your interactions and exported out your Xcode project, you could dive into the code to modify it as you wished, and build out a complete iOS app around it.

Visual programming environments opened up a new way of thinking for me about how I could use computers. I would no longer be constrained to using already written software as a user - I could create my own software even though I didn’t (yet) know the first thing about programming. I was able to explore the medium of computation through the lenses of things I was familiar with (music) or things that I had a desire to learn (interactive visuals).

Visual Programming environments can be extremely powerful tools - allowing end-users to have the ability to move a bit lower on the ladder of abstraction from just using software that someone else wrote for a particular domain or task.

The biggest power of these tools lies in their ability to literally draw connections between dynamic objects, allowing for a fast and intuitive development process. Additionally, the canvas nature of these tools allows for the program to be composed / organized in a spatial manner - you can see how the program controls from one object to the next. Unlike regular software development, the user does not have to keep all of these connections and state information inside of their head - they can just look at the canvas.

At the same time that I was learning these environments, I was taking a few CS classes in college, in addition to my required courses - and I absolutely hated them. The subject matter felt opaque, the professors were incredibly impatient with me, and in general the classes were very divorced from what I actually wanted to learn how to do - which was how to make things.

I doubt I would have eventually learned how to program were it not from exposure to these Visual Programming Environments - because they were visual and I could see the effect that my actions would have on the output, I could understand my agency in the act of engaging with computation.

While Visual Programming Environments are certainly not perfect - when creating something very complex in these environments, you can easily get a visually cluttered, tangled mess of connections that are impossible to parse through - the fact that they provide an easy path to being onboarded to interacting with computation is what makes them valuable for people who may not otherwise have been exposed to the process of creating software.

Learning More: