Objective-C Review for Swift Developers

I’ve been interviewing for new positions recently, and for one of the roles I interviewed for; was told it would be a good job to brush up on my Objective-C knowledge. I’ve been writing iOS and macOS apps primarily in Swift since it was launched in 2014; I’ve actually been writing software in Swift longer than I ever did in Objective-C. So, I spent some time reviewing Objective-C concepts and patterns; and thought it may be helpful to share my review note in the form of a blog post for anyone who may find themself in a similar circumstance.

This definitely is not a complete overview of the Objective-C language or the patterns and paradigms of programming in it, but it should be a good overview of some of the concepts in it that may come up during an interview.

What are Categories?

If you want to add a method to an existing class, you can use a category. The can be declared for any class, and can be used to split the implementation of a complex class across multiple source-code files.

@interface ClassName (CategoryName)

//add new methods here

@end

What are Extensions?

Extensions are similar to categories in that you they allow you to extend the functionality of a class. Unlike categories, they allow you to add your own properties and instance variables to a class. As such, they can only be added to a class for which you have the source code at compile time. The implementation of a class extension should be placed in the implementation file of the class who’s functionality you are extending.

@interface ClassName ()

// Add new properties and variables here

@end

What is a Protocol?

A protocol declares the methods that are required for a particular situation. If a class wants to adopt certain functionality that a protocol provides, it has to implement the methods that are part of the corresponding protocol.

@protocol NewProtocol

//list of methods for the protocol

@end

By default, all methods listed in a protocol are required. However, you can specify methods as optional:

@protocol NewProtocol

@required

//list of required methods for the protocol

@optional

//list of optional methods for the protocol

@end

Describe how automated reference counting (ARC) (including weak references) works.

A reference is any object pointer or property that lets you reach an object. When a reference is strong, the object will be kept alive in memory - it keeps the class instance that the reference points to from being deallocated. Whenever there are no remaining strong references to an object, the object will get deallocated.

However, strong references are not always the right thing to use when writing code. If two objects need to refer to each other, making both references strong would create a strong reference cycle, preventing either object from ever being deallocated. In this case, you would want to make sure one of the objects has a weak reference, which has no effect on the lifetime of the object - weak references are aware of objects, while strong references are owners of an object - allowing for objects to be able to be deallocated.

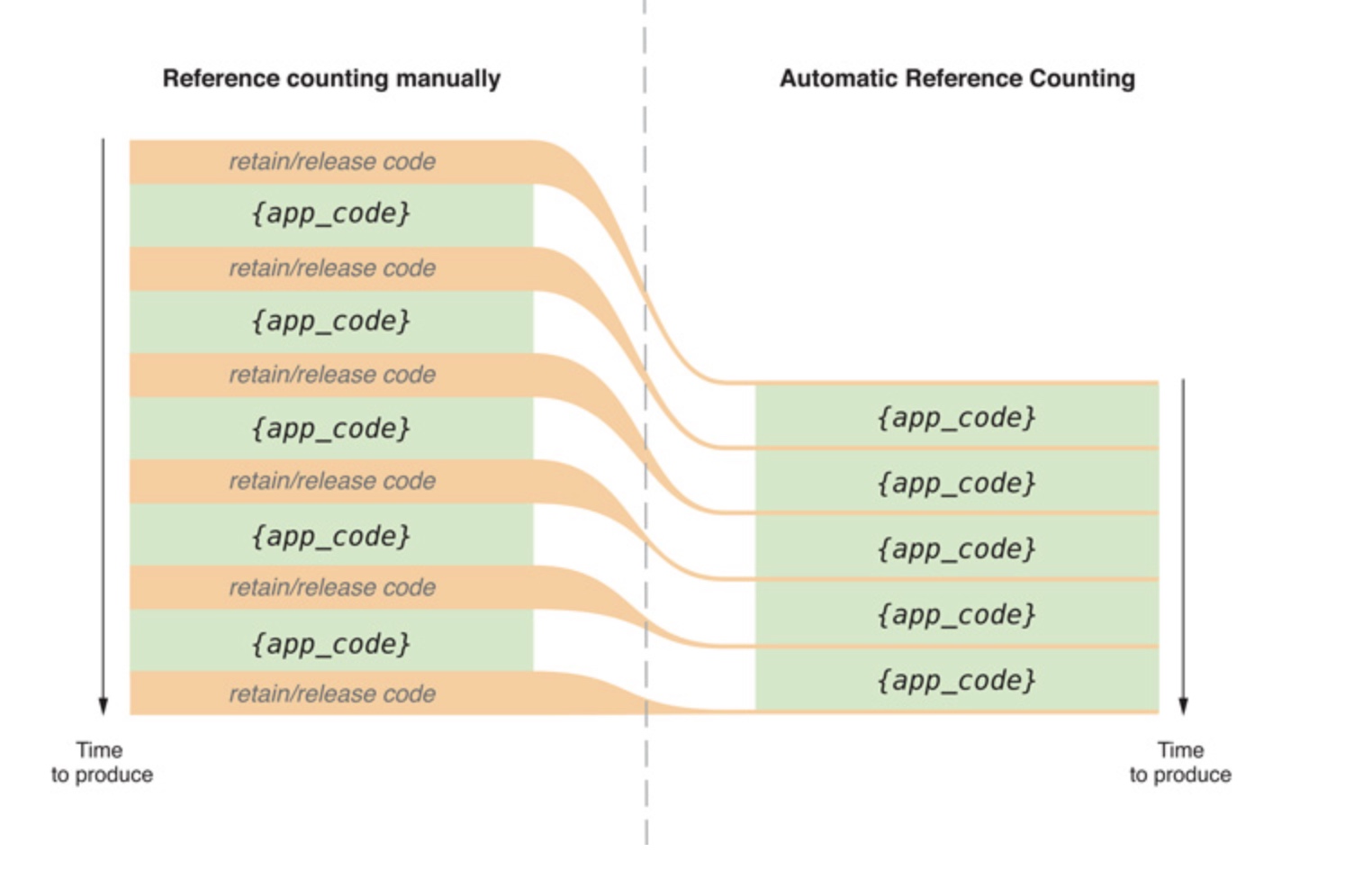

With Automated Reference Counting, the compiler inserts the object code messages retain and release into the source code, which will increase and decrease the reference count of the objects, when appropriate, at run time. Essentially, what ARC does is add in memory management handling code automatically when the code is compiled. When an object’s reference count reaches zero, the object gets marked for deallocation.

(from Apple’s Transitioning to ARC Release Notes)

Describe the various @property types

There are three attributes of properties that can be changed for a property:

Atomicity (whether an object returns valid data)

Properties are declared atomic by default. If a property is atomic, it’s guaranteed that if you try to read from it, you will get back a valid value.

nonatomic properties can return junk data, but accessing and setting them is faster than atomic properties

Access (who can access the property)

- readwrite means that anyone with access to the property can set and get it’s value. This is the default for properties.

- readonly properties can be read from, but not written to

Storage (how a property is referenced)

- An object with a strong reference will be kept alive in memory as long as there’s a reference to that object.

- A weak reference means that whenever existing references to an object are destroyed, the object will be removed from memory.

- Any property with the copy attribute logically copies any value assigned to it

Describe the Delegate Pattern

Apple’s Concepts in Objective-C Programming Guide defines a delegate as “…an object that acts on behalf of, or in coordination with, another object when that object encounters an event in a program”.

Methods that are required to implement the delegate pattern are part of a Protocol, which, as we saw earlier; is what encapsulates the methods to implement a specific functionality for an object.

The most common example of the Delegate Pattern in iOS development is the UITableViewDelegate methods. These methods govern how an instance of UITableView updates the ViewController that it’s part of. When you create an instance of UITableView and add it to your class, you are required to implement the following methods:

- (NSInteger)numberOfSectionsInTableView:(UITableView *)tableView

- (NSInteger)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView numberOfRowsInSection:(NSInteger)section

- (UITableViewCell *)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView

cellForRowAtIndexPath:(NSIndexPath *)indexPath

- (void)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView didSelectRowAtIndexPath:(NSIndexPath *)indexPath

- (CGFloat)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView heightForRowAtIndexPath:(NSIndexPath *)indexPath

These delegate methods govern not only the properties of the table-view, will also update whenever the user interacts with the table view in the app. If a user selects a row in the table view, then didSelectRowAtIndexPath is called. Depending on what the indexPath value is (which determines what row was selected, and therefore what table-view cell was selected), the view controller can then take the correct action based on what was selected.

A delegate’s property is always declared weak to ensure that no retain cycles are created. Since a delegate and its delegating object have to refer to each other, if both were marked as strong, a retain cycle would occur, and the objects may not be able to be deallocated using ARC. Marking the delegate as weak prevents this from occurring.

What are Notifications?

Notifications allow for messages to be sent from one object to another object even if the objects are not part of the same class, or delegates of each other at all. They behave in a broadcast fashion - you can broadcast out a message from anywhere in an app, and any object that is listening for that notification will hear it. The listener object can then do things like update its variables with data passed from the notification, or call a method when the notification is received.

Notifications are broadcast through the NSNotificationCenter.

Here’s what posting a notification looks like:

[[NSNotificationCenter defaultCenter] postNotificationName:@”EventOccurred” object:nil userInfo:nil];

In the ViewController that you want to receive the notification in, add an observer for it:

[[NSNotificationCenter defaultCenter] addObserver:**self**

selector:**@selector**(methodToCallNext:)

name:@"EventOccurred" object:nil];

Whenever the notification is received in the ViewController, the methodToCallNext will be called.

When the lifecycle of that ViewController is finished, remove the notification observer:

[[NSNotificationCenter defaultCenter] removeObserver:myObserver];

You can also pass objects:

NSDictionary *usernameDictionary = @{@”username”: @”narner”};

[[NSNotificationCenter defaultCenter] postNotificationName:@”UserNameUpdated” object:nil userInfo:usernameDictionary];

…and receive them via Notifications:

-(void) receiveNotification:(NSNotification*)notification

{

if ([notification.name isEqualToString:@"UserNameUpdated"])

{

NSDictionary *userInfo = notification.userInfo;

NSString *userName = (NSString*)userInfo[@"username"];

}

}

What are the tradeoffs between Delegates and Notifications?

Notifications result in loose-coupling between objects: an object that sends a notification does not have to know anything about any of the objects that may be listening for the notification, and likewise; the objects that are listening for a notification do not have to know anything about the object that may have sent the notification.

While this is very useful in terms of keeping objects de-coupled from one another; it can make things a lot harder to debug when code heavily relies on notifications for sending messages between objects.

If an instance of UITableView relied on notifications instead of a delegate pattern, then all the classes that use a table view in your app could choose different method names fo reach notification. This would make it hard to understand your code, as you would need to go and find the notification registration section to work out which method is called. With a delegate, it’s obvious: all classes that use a table view are enforced to be structured in the same manner.

On the other hand; a situation where notifications would be desirable to use would be in the login handling of an application - it would be impractical to couple all the various parts of an application that may need to know about an app’s login state to the login handler itself.

What are the types that can be written to a P-List file

A P-List (or “Property List”), is a file that stores serialized objects. These objects are encoded in a UTF-8 string. The following Foundation types can be written to a P-List:

- NSString

- NSNumber

- NSDate

- NSData

- NSArray

- NSDictionary

For further review, check out Apple’s Reference Article on P-Lists.

Describe how to correctly implement equality comparison for subclasses of NSObject.

@matt wrote an excellent post on NSHipster on the topic of equality in Objective-C; I’ll briefly summarize some of they key points of it here.

In Objective-C, using the == operator checks to see if two objects point to the same location in memory; in other words, whether or not they have the same identity. isEqual, in its base implementation, simply tests for whether objects have the same identity in the same way that == does.

In the code below (from the NSHipster post), we have two objects, a and b. They are distinct objects that occupy distinct places in memory - they, therefore, do not have the same identity, and are not equal to each other.

NSObject *a = [NSObject new];

NSObject *b = [NSObject new];

BOOL objectsHaveSameIdentity = (a == b); *// NO*

BOOL objectsAreEqual = ([a isEqual:b]); *// NO*

As Matt points, out, however, “…some NSObject subclasses override isEqual: and thereby redefine the criteria for equality.” NSValue is an object that encapsulates a value - if you compare two NSValue objects with ==, you’ll get a result stating that they are not equal, because they occupy distinct spaces in memory, though their values are the same. If you compare them with isEqual, you’ll get a result stating that they are equal, because their values are the same, though they occupy different spaces in memory.

NSPoint point = NSMakePoint(2.0, 3.0);

NSValue *a = [NSValue valueWithPoint:point];

NSValue *b = [NSValue valueWithPoint:point];

BOOL valuesHaveSameIdentity = (a == b); *// NO*

BOOL valuesAreEqual = ([a isEqual:b]); *// YES*

Grand Central Dispatch and NSOperation

Dispatch (also known as Grand Central Dispatch) is a lower-level API for managing concurrent operations. The system builds a thread pool that has a set number of threads that are available for tasks to be run on. As a developer, you can rely on Dispatch to handle the creation of threads, without having to manually create and assign them yourself. When you add blocks of code to be executed to a DispatchQueue, Dispatch will decide what thread to execute them on for you.

DispatchQueue is a First-In-First-Out queue that can be run on either the main thread or a background thread in your application. Tasks added to a DispatchQueue can be run either synchronously or asynchronously.

There are several levels of Quality of Service levels that you can specify for on a DispatchQueue, depending on the type of task that you are using a DispatchQueue for:

- User Interactive - The quality-of-service class for user-interactive tasks, such as animations, event handling, or updating your app’s user interface.

- User Initiated - The quality-of-service class for tasks that prevent the user from actively using your app.

- Default - The default quality-of-service class.

- Utility - The quality-of-service class for tasks that the user does not track actively.

- Background - The quality-of-service class for maintenance or cleanup tasks that you create.

- Unspecified - The absence of a quality-of-service class.

This article from TheSwiftDev goes into some great detail on the mechanisms behind Dispatch, and some of the principles of Synchronous and Asynchronous programming.

There’s another tool available for working with threaded programming, NSOperation. NSOperation is “an abstract class that represents the code and data associated with a single task”. NSOperation is actually a bit higher level than DispatchQueue, as it uses DispatchQueue under the hood.

Just like DispatchQueue, NSOperation also allows for specification of Quality of Service levels and priority levels.

The NSHipster article on NSOperation states that “…For one-off computation, or simply speeding up an existing method, it will often be more convenient to use a lightweight GCD dispatch than employ NSOperation.” Since NSOperation can be cancelled, scheduled, and have it’s operational state observed, it’s probably best for more “heavy-duty” threaded tasks.

What is Key-Value Observation?

Key-Value Observation allows for objects to monitor for changes of values in a different object. For example, if you had a Weather class, you could have it observe the changes in property values in a Temperature, Humidity, or Precipitation class - keeping the Weather class up-to-date with whatever the latest weather parameters are.

So, let’s say you have a Temperature class with the following properties:

@property (nonatomic, strong) NSFloat *lowTemperature

@property (nonatomic, strong) NSFloat *highTemperature

Your Weather class could observe the properties of the class like so:

@immplementation Weather

- (void)observeChanges:(Temperature *)temperature {

[person addObserver:**self**

forKeyPath:@"lowTemperature"

options:NSKeyValueObservingOptionNew

context:nil];

}

- (void)observeValueForKeyPath:(NSString *)keyPath

ofObject:(id)object

change:(NSDictionary<NSKeyValueChangeKey,id> *)change

context:(void *)context {

if ([keyPath isEqualToString:@"lowTemperature"]) {

NSNumber *ageNumber = change[NSKeyValueChangeNewKey];

NSInteger lowTemperature = [lowTemperature integerValue];

NSLog(@"New low temperature is: %@", lowTemperature);

}

}

What is the purpose and function of Key-Value Coding (KVC).

Key-Value Coding is what makes things like Key-Value Observation possible. It’s a “…fundamental concept that underlies many other Cocoa technologies, such as key-value observing, Cocoa bindings, Core Data, and AppleScript-ability.” (from Apple’s Key-Value Coding Programming Guide). Key-Value Coding allows for an object’s properties to be accessible through string parameters which, as we saw above; is the mechanism that Key-Value Observation uses to allow for one object to observe the property values of another object.

Any object that inherits from NSObject (so, everything; as that’s the root base class off all objects in Objective-C).

What are the disadvantages of the Singleton Pattern?

The Singleton Pattern restricts the instantiation of a class to a single instance. That single object is able to be accessed globally throughout your app by other classes and objects - data can be shared between different pieces of code without having to pass the data around manually.

The problem with the Singleton Pattern is that it makes unit testing difficult - since the Singleton relies on a global application state, it’s impossible to completely isolate classes that interact with the Singleton instance. As a result, these classes can’t be truly isolated from one another to ensure testing of their independent functions. Additionally, the Singleton pattern encourages excessive coupling between classes - since the class that needs to access the Singleton is bound to a specific interface, making it not only more difficult to test, but also making production code more fragile.

Describe how message passing works

Messaging is the terminology for invoking methods on an object. In Objective-C, objects aren’t called, but rather; messages are sent to them.

-[<RECEIVER> <SELECTOR>];

In the code above, the receiver is the definition or instance of a class, and the selector is the name of the method that you want to invoke. When the receiver object receives the message of the selector, it calls the corresponding method.

What is the difference between #import vs #include?

#import is used to ensure that a file is only ever included once in a project. Both lines of code below will include the file that you want in the project, but the second will make sure it’s only included once:

#include <Framework_name/Header_filename.h>

#import <Framework_name/Header_filename.h>

Thanks to Warren Moore for proof-reading this post.