Jazz, Gestures, and Open-Source - Why & How I Learned to Code

Inspired by a conversation with Diana Berlin, I wrote about what motivates me as a technologist, and the personal story behind why and how I learned to code.

I published the piece on Medium here, and am including it below as an archive:

There’s been lots of discussion lately on how many people working as software developers “started off doing something else” before they learned to code…often meaning that they studied something other than computer science in college.

I count myself as one of those folks who never intended on becoming a software developer, but found their way into it anyhow.

I originally went to college on a music scholarship. My instrument of choice was electric jazz bass. Frankly, I was much better suited to playing in rock bands rather than reading lead sheets — but that’s a story for a different time.

My major was Music Technology, which was housed in Capital University’s Conservatory of Music. My classes focused on electronic music, studio recording, sound for media, and a fair bit of music theory, sight-singing, and keyboard practice.

I spent a lot of time in a practice room with a bass , my metronome ticking away while I learned the changes to tunes like “St. Thomas” and “So What.”

I should note that during the summer before I started college, I worked at a factory — the Superior Dairy Plant in my hometown of Canton, Ohio. Most of my 8-to-10-hour shifts consisted of lifting crates of milk that were then shipped out to grocery stores. During Winter Break after my first semester, I went home and worked a few shifts at the dairy again.

Fast forward to the end of my first year as a Music major: My wrists hurt. They hurt a lot. When I would try to play bass, they felt extremely tender. I went to the doctor, and he said I had tendinitis, which meant I had to wear wrist braces for several months and go through some occupational therapy.

I wasn’t allowed to play bass for that entire summer, nor for the following semester.

I eventually switched my degree from a Bachelor’s of Music to a Bachelor’s of Arts, but I still continued with studying Music Technology.

Now that I wasn’t in a practice room much anymore, I had a lot of time to think — and one thought that I couldn’t shake off was how grateful I was that I at least had hands! I knew that I would still be able to play music at some point again. My thoughts, though, kept drifting to musicians who sustained even more serious injuries than I did or otherwise couldn’t play music due to some sort of accessibility issue.

I started doing some research, reading journal articles and conferences from music-therapy conferences, as well as NIME (the New Instruments for Musical Expression conference). I learned as much as I could about how programmers, engineers, and designers were leveraging technology to allow people with various types of disabilities express themselves through music.

I decided that I wanted to work on making instruments that would help everyone express themselves through music.

I decided that this was an area in which I wanted to contribute.

I eventually came to realize that I needed to learn how to program — so, I signed myself up for some classes in the school’s Computer Science department. I had always loved learning about technology. As a kid, I spent time building model rockets, taking apart any electronics I could get away with disassembling, and going with my Papaw, a broadcast engineer, as he drove around the Northeast Ohio area conducting repairs at radio transmitter towers.

I did not do very well in those classes at first.

For whatever reason though, I kept at it. Call it a gut instinct, if nothing else.

I decided that I wanted to go to graduate school so that I could work on creating accessible music technology. During my senior year of college (2012), I was accepted to the MSc (by research) program in Music Technology at the University of York’s Department of Electronics in England.

My original goal was to develop an iPad app for making music, designed specifically at kids who may be in music therapy programs. At this point, I had started to dip very slowly into iOS development: I had an iPhone, so it seemed like a fairly logical next step to take.

My advisor, Dr. Andy Hunt, wisely helped me to narrow the focus of my research goals — my original idea was fairly broad…and, frankly, somewhat beyond the programming skills I had at that time. I settled on how multi-touch devices afforded the potential for engaging, gestural interfaces for interacting with music. You can read the full thesis here if you’re interested; here’s the abstract as a teaser:

“The thesis explores the use of multi-touch gestures in the use of interactive music apps run on mobile devices. With the growing popularity of mobile, multi-touch devices such as the iPad, more and more people have the chance to interact with music in a creative setting. However, many of these apps are based on traditional analogue music equipment, employing metaphors to physical interaction elements such as rotary knobs and faders. User preference for musical interaction is researched. Three apps were developed for this investigation: two apps employ skeuomorphic UI elements (rotary knobs and faders), and the third employs multi-touch gestures. All three apps allow the user to interact with a granular synthesizer. User tests show that if users want an app that will allow them to explore music in a manner they would describe as “intuitive, interactive, creative, and playful”, then a multi-touch gestural app is the preferred option. However, if users want to be able to intricately modify and edit music, then an app implementing a skeuomorphic design paradigm is the preferred option.”

After moving back to the US and finishing up some final corrections, my thesis was finished, and my MSc was complete.

While looking for jobs, I became connected with Aurelius Prochazka, who was then working on a then-not-yet released version of AudioKit. The goal of AudioKit was (and still is) to create a library for Mac and iOS developers to easily add interactive audio functionality to their apps without having to dive into the somewhat arcane world of Core Audio and low-level Digital Signal Processing programming.

At this point, I was still exceptionally green as a developer — I really didn’t know what I didn’t know. Luckily, though, with Aure’s help, I was able to use working on AudioKit as a bridge between a world I knew intimately (electronic music synthesis) and a world I was trying to come to terms with (software development).

Having that bridge was invaluable. Working with Aure on AudioKit was really nothing short of pivotal in learning how to code.

A few months after I started my first software development job, I read about the work shown at that year’s Google I/O. I was blown away when I saw Ivan Poupyrev present Project SOLI.

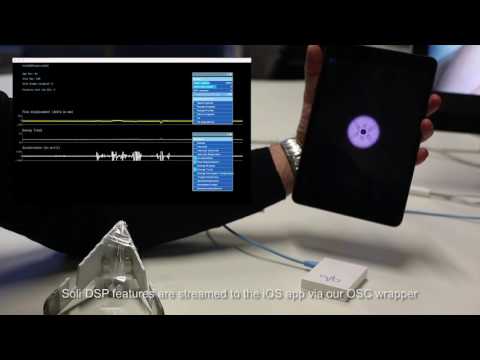

If you’re not familiar with it, SOLI is a radar-powered sensor developed by Google ATAP for detecting fine-grained gestures. I immediately saw its potential for use in creating new musical instruments.

Google stated they would be opening up a program for outside developers and researchers to build applications using SOLI. My friend Paul Batchelorand I collaborated on building instruments using SOLI. Our experiments, together with the work of Francisco Bernardo, were published in a paper for the NIME 2017 conference. You can check out some of the demos in the video that accompanied the paper below:

Collaborating with others and side-projects have been critical for me in learning how to code. Whether working on an open-source project like AudioKit, or learning complex new technology like Soli, having other people to learn from and bounce ideas off of has been very helpful to growing as a developer.

What keeps me motivated to keep learning and growing as a developer is finding ways to make interacting with technology more accessible, natural, and delightful — I want to help people be more creative through the use of technology through better tools and modes of user interaction.

Please feel free to reach out if you share these motivations — I’d love to hear from you.